2023. 1. 6. 09:08ㆍ아티클 | Article/칼럼 | Column

Architecture Criticism

Sitting with Seung H-Sang; Around the Table of Architecture

휴머니티란 결코 홀로 얻을 수 있는 것이 아니며 공공에 작업을 내어놓는다고 해서 얻을 수 있는 것도 아니다. ‘공공 영역으로의 모험’에 자기의 삶, 자기 자신을 던졌을 때만 얻을 수 있는 것이다.

- 한나 아렌트(Hannah Arendt), 「칼 야스퍼스 찬사 Karl Jaspers: A Laudatio」, 1958

승효상의 건축에 대한 이 글을 한나 아렌트의 인용구에서 시작하려 한다. 아렌트와의 연결 고리는 필자의 발상이 아니라 승효상 자신이 제시한 것이다. 최근 몇 년간 건축과 도시 정책 영역의 공인으로 활동하면서 그 명분으로 스스로 취한 아렌트의 말이다. 아렌트가 친구이자 스승이었던 야스퍼스의 독일도서전 평화상 수상을 축하하며 쓴 축사의 한 구절이다. 평화상의 정신에 따라 아렌트는 야스퍼스를 학자로서만이 아니라 공적인 영역의 활동가로서 치하했던 것이다. 승효상은 2014부터 2016년까지 초대 서울시 총괄건축가로 활동했고 현재 대통령 직속 국가건축정책위원회 위원장직을 맡고 있다. 공식적인 직책과 폭넓은 영향력을 통해 그는 우리나라의 건축 관행을 바꾸어 나가는 중이며 새로운 제도와 정책 수립을 이끌고 있다. 현재 대부분의 주요 도시에서 시행되고 있는 총괄 건축가 및 공공 건축가 제도는 일상생활과 밀착된 공공디자인에 대한 비전을 토대로 공공 건축사업의 발주 방식을 바꾸고 있다. 정책결정자들이 동네 단위의 재생에 관심을 갖도록 설득하고, 서울도시건축비엔날레가 탄생할 수 있도록 하는 견인차 역할을 하기도 했다. 서울도시건축비엔날레는 도시 거버넌스와 직결된 새로운 종류의 국제 비엔날레로서 도시와 건축에 대한 국내외 전문가와 함께 일반 시민, 관료와 정책입안자의 인식을 바꾸어 나가는 역할을 하고 있다. 국가건축정책위원회는 건축사의 위상과 건축 본연의 역할을 훼손하는 입찰과 심의 제도의 개혁을 추진하고 있다. 시장, 도지사, 장관, 그리고 대통령과 직접적인 소통 채널을 확보한 그는 많은 공공 프로젝트와 건축 정책의 큰 방향을 잡는데 역할을 하고 있다. 승효상이 우리나라에서 가장 영향력 있는 건축가라는 것은 명백한 사실이다.

최근 공공부문에서 활동하기 전에 이미 그는 한국에서 가장 잘 알려진 건축가였다. 베스트셀러 작가이며 건축의 역할에 대한 대사회적 발언을 했던 명사로 알려져 있다. 국립현대미술관 ‘올해의 작가’로 선정된 최초이자 유일한 건축가다. 물론 많은 건물을 설계한 건축가이다. 세대적인 구상으로 말한다면 해방 후에 태어난 탈식민지 시대의 첫 작가군에서 비교적 어린 축에 속한다. 한국이 1990년대 이후 민주화 시기에 진입하고 이미 괄목의 경제 성장을 이룬 시기에 건축가로 독립했다. 이런 그의 이력을 언급하는 이유가 단지 한 건축가를 칭송하려고 하는 것은 물론 아니다. 집을 설계하는 건축가로서만 아니라 시대와 함께, 복잡한 사회 속에서 살아가는 인물로서 승효상에 주목하는 이유는 문명과 사회 속에서 건축의 위상을 생각하기 위함이다. 건축을 이야기할 때 우리는 흔히 완공된 건물, 그리고 건물의 설계자로서 건축가만 말하기 일쑤다. 그러나 사회 속의 존재로서 사람에 대해 이야기해야 하지 않는가? 서두에 인용한 한나 아렌트의 말, 승효상이 즐겨 사용하는 인용구로 돌아가 보자. 여기서 아렌트가 제기하는 핵심 문제는 작업과 삶의 관계다. 승효상이 아렌트를 인용하는데 주시해야 할 재미있는 사실이 있다. 그 동안 아렌트의 이 말을 인용할 때 승효상은 ‘공공에 작업을 내어놓는다고 얻을 수 있는 것이 아니다’ 부분을 생략했다. 왜 그랬을까? 휴머니티를 획득한다는 거창한 명제에 작품을 만드는 건축가의 작업으로는 부족하다는 아렌트의 말이 불편했던 것일까? 그리고 그에 앞서 작업과 삶에 대한 아렌트의 입장은 무엇인가? 아렌트의 말을 전체적으로 곱씹어 보자. 승효상의 ‘작업’과 그가 진행하고 있는 ‘공공 영역으로의 모험’의 관계에 대해 생각해보자.

모든 건축가와 마찬가지로 승효상에게는 두 가지 세계가 있다. 한편에 그의 작업이 있다. 물리적인 공간 속의 사물, 그가 설계하고 구현한 건물들이 그것이다. 다른 한편에 아렌트가 말하는 ‘사람됨’, 다시 말해 공적영역에 온전히 내던져진 인격이 있다. 아렌트에 이어 사회이론가 김현경은 ‘사람’에 대한 정의를 다음과 같이 내린다.

사람다움은 우리가 원래 가지고 태어났거나 (그래서 잃지 않으려고 애써야 하거나) 사회화를 통해 획득해야 하는 본질이 아니다. 그보다 사람다움은 우리에게 있다고 여겨지며, 우리 스스로 가지고 있는 체하는 어떤 것, 서로가 서로의 연극을 믿어줌으로써 비로소 존재하게 되는 어떤 것이다.

다시 말해서 인격은 본질이 없는 사회적 현상이다. 우리는 모두 인간으로 태어나지만 ‘사람’이 되기 위해서는 남의 인정을 받아야 한다. 사회 구성원 개개인의 수행과 이들 간의 상호관계를 통해서 만들어지는 것이다. 실제로 승효상은 건축주, 언론, 정계, 그리고 건축-문화 영역의 동료들과 폭넓은 관계를 가지면서 활동한다. 사람 간의 상호 관계 속에서, 우리가 속칭 ‘인맥’이라고 하는 관계망 속에서 일관되면서도 다면적인 인격을 형성한다. 그런 만큼 그는 프로젝트마다 여러 가지 역할을 수행해 왔고 그래서 각각의 프로젝트가 전하는 스토리가 다르다.

다만 짧은 글에서 승효상의 작업을 모두 논할 수는 없고, 또 그것이 갖는 많은 속성들에 대해 두루 이야기할 수도 없는 상황이다. 필자는 승효상의 작업에서 한 가지 핵심 요소를 주시하고자 한다. 물리적 존재로서, 사유의 기제로서 ‘바닥’에 주목한다. 2007년에 출간된 졸고 「감각의 단면」에서 이미 승효상의 건축에서 바닥의 표현력, 공간 구성에서의 역할을 역설한 바 있다. 지난 25년 그의 작업이 보여준 일관된 양상이다. 여기에 세 가지 사례를 중심으로 이야기 하고자 한다. 프로그램과 규모 면에서 다르고, 도시적 맥락도, 건축주도 다 다른 파주출판도시, 노무현 묘역, 사유원이 그 대상이다. 다양한 작업을 구현하는 건축가로서, 그리고 다면적인 인격체로서 승효상이 프로젝트를 이끌어가는 방식을 살펴보도록 하겠다.

파주출판도시, 컬처스케이프

파주출판도시는 서울에서 30km, 비무장지대에서는 불과 10km 떨어져 있는 출판산업단지다. 출판산업의 위기, 특히 유통 체계의 문제를 풀어야 한다는 목표로 이기웅 대표를 중심으로 하여 중소형 출판사 대표들이 모여 책의 도시, ‘북시티’를 만들겠다는 야심찬 발상을 하였다. 출판도시 프로젝트는 10년간 우여곡절을 거치다가 승효상, 플로리안 베이겔(Florian Beigel), 민현식, 김종규, 김영준, 필립 크리스토(Philip Christou)로 구성된 도시설계팀의 제안이 추진의 기반이 되면서 현재의 출판도시 모습을 갖추기 시작했다. 160만㎡에 달하는 1단계는 국내 최대 규모의 출판 물류센터, 130개 출판사, 57개 인쇄업체, 그리고 호텔을 포함하고 있다. 2007년 1단계가 성공적으로 마무리된 후 1단계보다 약간 작은 규모로 영상산업을 포함한 2단계가 현재 진행되고 있다. 승효상은 파주출판도시에 교보문고, 명필름, 디자인 비타 등 몇 개의 건축 프로젝트들이 있다. 개별 건물의 건축가로서의 그의 역할보다 더 주목할 것은 민간의 건축 설계 발주 시스템, 그리고 설계안들이 따라야 하는 지침을 만드는 지난한 과정에서 그의 역할이다. 승효상은 건축가로 활동을 했지만 통념적인 건물의 디자이너와는 다른 종류의 일을 한 것이다. 파주출판도시가 혁신적인 문화 클러스터가 될 수 있었던 것은 승효상의 비타 악티바(vita activa)’, 한 ‘사람’의 적극적인 사회 활동 때문에 가능했던 것이다.

파주출판도시의 초기 추진 단계에서 승효상은 두 달 동안 거의 매일 파주를 찾아가 출판사 대표, 정치인, 공무원, 동료 건축가들을 만났다고 한다. 출판인들과 함께하는 여러 번의 국내외 건축 답사를 기획했고, 함께 다니며 건축의 역할에 대한 인식을 새롭게 하고자 했다. 통념과 관례를 벗어나 새로운 건축 체제를 설득하는 과정에서 많은 세미나와 워크숍, 전시회를 기획했다. 이러한 모든 활동에 힘입어 출판계와 건축가들은 자체적인 설계 가이드라인에 합의하게 되었다. 랜드스케이프 어버니즘(landscape urbanism)의 영향을 받았지만 외부 공간의 공유 영역, 심학산과 한강을 향한 공동의 전망, 건축 재료의 범주, 등의 문제를 중심으로 건축 유형에 기반을 둔 설계 지침을 따르도록 했다. 더 나아가 민간 건축주들이 마음대로 설계 계약하는 것이 아니라 지침에 대한 이해가 있는 건축가 풀에서 선정하여 계약하도록 합의를 보았다. 이런 지침은 법적 구속력이 전혀 없는 출판인들의 자발적 의지에 기반한 것이었다. 일정한 자격을 갖춘 건축 사무실의 풀을 만들어 일상적인 도시 공간까지 공공의 가치를 증진하는 설계를 확보하겠다는 생각은 지금 여러 지자체의 공공건축가 제도의 전신이라 할 수 있다.

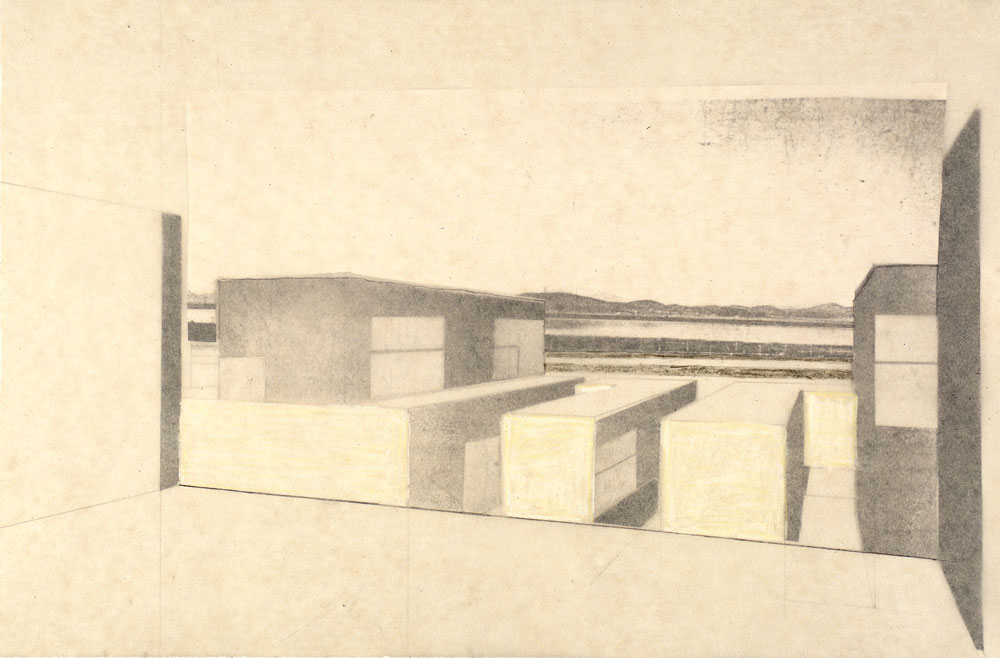

파주는 사실상 혁신적인 출판도시를 만들 수 있는 여건이 조성되어 있지 않았다. 한국토지공사가 작성했던 도로와 인프라 계획을 바꿀 수 없는 상황이었다. 단지 내 주택이 160호에 불과했으며, 군사지역 특성상 4층 이상의 건축물이 금지되어 있었다. 대부분의 출판사들은 충분한 재원이 없었고 산업단지의 복합용도 개발이 허용되지 않아 새로운 건축적 가능성은 사실상 제한되어 있었다. 파주출판도시를 처음 발상했을 때 상상할 수 없었던 책의 종말이 실제로 도래한 지금에도 혁신 도시의 비전은 계속 지켜지고 있다. 두 세대에 걸친 한국 건축가들에게 많은 설계 기회를 제공했고 우리나라뿐만 아니라 세계 최고의 건축가들이 작업을 하는 건축 전시장이 되기도 했다. [그림 1] 인근 상업 및 주거지역이 계속 확장하고 있고 남북관계가 여전히 불투명하지만 변하지 않을 수 없는 상황이다. 파주출판도시는 미래의 사회•공간•경제의 비전을 전제로 계속 진화하는 중이다.

지금까지 파주출판도시가 만들어지는 과정에서 ‘사람’으로서 승효상의 활동을 요약했다면, 지금부터 파주출판도시에 작용된 건축적 기제를 살펴보도록 하자. 이 점에 있어서는 설계 지침을 만들었던 팀의 핵심 멤버였던 플로리안 베이겔의 역할에 주목해야 한다. 파주출판도시 설계 가이드라인을 발상하는데 있어서 플로리안 베이겔의 아이디어와 스케치가 결정적인 역할을 하였다. 베이겔은 부지 전역을 아우르는 다양한 지평선, 즉 한강의 지평선, 습지의 수위, 사용자의 눈높이에서 본 먼 지평선을 설계 지침의 기반으로 삼았다. [그림 2] 조세프 그리마(Joseph Grima)가 한국에서 플로리안 베이겔의 작업에 관하여 언급한 것처럼 “파주출판도시 계획은 평면이 아니라 단면의 문제였다.”

승효상이 베이겔과 파주 작업을 하기도 전에 바닥이 이미 그의 건축에서 중요한 요소였다는 것은 주지의 사실이다. 바닥, 또는 기단은 한 건축가의 작업을 넘어 한국 건축의 중요한 요소이기도 하다. 경사가 많은 우리나라의 지형 특성상 경사지를 정리하고, 향을 잡고 채의 자리를 구획하면서 단면을 다루는 솜씨가 성숙해졌다. 승효상은 베이겔의 방법론을 수용했지만 지평선에 대한 그의 입장은 근본적으로 다르다는 점을 주목해야 한다. 투시도에 기반을 둔 서양의 전통과 본인이 갖고 있는 현상학적 입장에 따라 베이겔은 보는 이와 보는 대상에 함께 내재된 통합적인 지평선이 있다고 믿는다. 승효상에게는 그런 초월적인 지평선이 없다. 그에게 파주출판도시의 지평선은 구체적인 역사와 그 땅에 한정된 현실이다. 문화적 풍경cultural landscape을 변형하여 만들어낸 ‘컬쳐스케이프 culturescape’라는 승효상의 조어가 말해주듯이 지평선은 건축과 사회의 행동 근거가 될 수는 있지만 보편성이 있거나 근원적인 것이 아니다. 하나의 통합된 지평이 아니라 장소마다 다른 지평선이 있다는 전제는 서울에 대한 승효상의 비전에서도 드러난다. 그가 그리는 서울은 다층적인 도시로서 산세와 자연의 지면뿐만 아니라 근대가 만들어낸 고가도로, 인공 데크, 지하 공간을 모두 아우른다. [그림 3] 그가 기회마다 이야기하듯 서양의 도시에서는 보기 힘든 공간 구조이자 사회적 감수성이다. 승효상한테 지평선, 단면, 바닥은 구체적인 땅의 문제이자 사람이 경험하는 감각의 영역이다. 이런 의미에서 승효상은 원리주의자가 아니다.

노무현 대통령 묘역, 사물의 시간

노무현 묘역만큼 작업과 사람의 관계가 진하게 얽혀 있는 건축 프로젝트는 없을 것이다. 퇴임 후 철통 같은 경호를 받으며 도시 속 사저에서 지낸 전직 대통령들과는 달리 노무현 대통령은 고향 봉하 마을로 돌아갔다. 그가 태어난 작은 마을에서 새로운 공동체를 만들어보는 것이 그의 꿈이었다. 살림집을 새로 짓고, 농지와 농가들을 개선하고, 방문객을 위한 상점과 편의시설, 박물관으로 재단장한 생가를 정비하여 공공의 장소를 만들어가고 있었다. 하지만 귀향 직후 가족과 측근들이 검찰의 수사 대상이 되었다. 법정과 매체에서 오랫동안 수모를 당해야 하는 상황이었다. 그가 가꾸어 온 민주 사회의 유산이 진흙탕 속에서 파괴되어 가는 것을 볼 수 없어 노무현은 스스로 목숨을 끊었다. 그의 삶과 죽음에 대해 논란이 끊이지 않지만 자신의 죽음을 통해 그의 생각의 힘을 보전할 수 있다고 믿었던 것 같다.

노무현 대통령은 국립묘지에 안장되지 않겠다는 의지를 유언에서 밝혔다. 그의 서거 직후, 고인의 뜻을 실현하기 위해 ‘아주 작은 비석 건립위원회’가 구성되었고 여기서 묘역의 건축가로 승효상이 선정되었다. 정치 역학이 휘몰아치는 가운데 승효상의 대담한 설계안이 실현된 것은 일종의 기적이라고 할 수 있다. 한국 현대사의 비극적인 사건으로 한 자리에 모이게 된 이들의 의지를 보여주는 증거이다. 노무현의 참여정신에 따라 묘역은 예술가와 작가, 학자, 그리고 1만5천개의 박석에 슬픔과 희망의 메시지를 남긴 시민들이 함께 만들었다. 2010년 봄, 묘역이 1차적으로 완공되었다. 노무현 묘역이 조성된 지 10년, 기단을 밟은 사람들이 천만명이 훌쩍 넘어섰다.

승효상의 여러 프로젝트와 마찬가지로 노무현 묘역은 바닥의 미학이 지배한다. ‘지문(地文)’이라는 건축론을 통해 설파하듯이 승효상은 땅으로부터 건축의 요소를 추출하려고 한다. 기존의 수로와 도로, 좁은 길, 주변 산세의 등고선, 인접한 농지의 패턴은 묘역이 만드는 새로운 땅의 물리적인, 그리고 개념적인 하부 구조를 제공한다. 주변 산과 묘역의 경계를 가르는 낮고 긴 코르텐 담도 수직 벽체이기 보다 경계를 가르는 기단의 경계 역할을 한다. 유일한 수직 요소는 하늘이 어두워질 때 비석을 밝혀주는 조명등이 내장된 깃대다. 첫 스케치부터, 첫 발상부터 승효상은 기단이 건축의 모두였다. 긴 세월 만들어진 봉하의 지세와 풍광이 있다. 건축가로서 그의 책무는 새로 만들어지는 바닥이 그 일부가 되도록 하는 것이었다. [그림 4]

바닥을 가까이하는 작업은 거대한 스케일과 영웅주의를 비판하는 ‘반모뉴멘트(counter-monument)’와 비슷한 속성을 갖고 있다. ‘반모뉴멘트’는 1990년대 초 제임스 영(James Young)이 독일 홀로코스트 기념비를 통찰하는 과정에서 그가 만들어낸 말이다. 제임스 영은 반 기념물의 주요 특징을 시간을 전용하는 방식에서 찾았다. “세월은 경직된 기념비를 조롱한다. 사물로 존재하기에 영원히 진리를 담지하고 있다는 주제넘은 기념비를 조롱한다. …영원할 것만 같은 기념물처럼 기억을 자극하지만 필연적으로 변하는 자신의 모습에 주목하게 한다. 세월이 흐르면서 기억 그 자체가, 불가피하게, 심지어는 본질적으로 진화한다는 사실을 말해준다.” 제임스 영의 통찰과 같은 맥락에서 승효상은 요헨 게르츠(Jochen Gerz)와 에스더 샬레브-게르츠(Esther Shalev-Gerz)의 하르부르크 반나치 기념비(Harburg Monument against Fascism)를 자주 언급한다. 시간이 지나면서 땅 속으로 차츰 없어지는 검은 기둥, 건물은 반드시 없어진다는 사실을 상기시켜준다는 점에서 승효상에게 중요한 프로젝트이다. [그림 5] 하르부르크 기념비에 비하면 노무현 묘역은 상대적으로 더 긴 기다림의 시간을 전제로 만들어 졌다. 기단을 밟는 발걸음에 결국 박석에 새겨진 문구들이 언젠가는 지워진다. 봉하를 찾는 사람들이 많을수록 박석에 새겨진 슬픔의 말들이 더 빨리 없어질 것이다. 비석의 강판에 새겨진 노무현의 말 ‘깨어 있는 시민의 조직된 힘’, 조금씩 마모되어 없어지는 바닥이 변하지 않는 큰 기념비보다 더 진하게 그 힘을 말해준다.

영구적인 기념비를 거부한다는 점에서 하르부르크의 홀로코스트 기념비와 봉하의 노무현 묘역이 뜻을 같이 한다. 그러나 건축 형태에 대한 태도가 아주 다른 프로젝트들이다. 하르부르크의 반모뉴멘트가 전통을 역전시키고 주변 맥락에서 이탈했다면, 노무현 묘역은 한국의 옛 전통을 불러들여 기존의 랜드스케이프와 조화를 찾는다. 국가가 만드는 기념비와 달라 낯설게 느껴질 수 있다. 하지만 역사에 반기를 드는 홀로코스트 기념비와 달리 노무현 묘역은 옛 것을 되찾고 살려내려고 한다. 승효상은 종묘의 수평 기단에서 영감을 얻었다. 폭 109미터, 깊이 69미터, 낮게 깔린 종묘의 화강암 기단은 사람이 어떻게 바닥과 관계를 맺으며 기억을 현재에 실천하는지를 보여준다. 위로 솟구치지 않는 인류 문명의 독특한, 그리고 위대한 기념비다. [그림 6] 서구인들은 지면을 불결하다고 생각했다. 땅과 거리를 두고 직립한 인간 형상을 문명과 동일시하였다. 이와 대조적으로 우리의 생활은 바닥과 친밀하다. 한국의 전통에 대한 승효상의 경외심은 묘역의 바닥에 새겨진 텍스트에서 다시 확인할 수 있다. 기단 박석에 새겨진 말들은 기억을 보전하는 방식이자 수평면에 의미를 새기는 아시아적 서예전통을 확인하는 건축이다. 노무현 묘역은 한편 안정적이고 보수적인 일단의 관습에 기대는 프로젝트이다. 동시에 위로 올리고 공간을 에워싸려는 서구의 전통과는 아주 다른 건축이다.

이처럼 전통을 수용하는 승효상의 태도는 건축이 땅에 자리를 찾는 방식에서도 드러난다. 파주출판도시와 마찬가지로 노무현 묘역 또한 컬처스케이프이다. 낮게 깔린 평평한 바닥은 상대적으로 크고 영구적인 기억을 간직하는 산세에 눈을 돌리게 하고 그 힘을 증폭시킨다. 노무현 묘역은 특정한 인간성을 간직한다. 가까운 부엉이 바위, 먼 봉화산, 그리고 작은 마을의 풍경 너머로 우리의 정신과 감성을 확장시키는 전망 속에 함께 있다. 그곳을 찾는 이들은 여러 가지 자세를 취하게 된다. 기단을 밟고, 고개를 숙여 기단에 새겨진 글귀를 읽는다. 무릎을 꿇어 참배한다. 산이 보이는 곳이며 산에서 내려다보이는 곳이다. 노무현 묘역은 가르치려 들지 않는다. 한 톨의 오만함 없이 우리에게 질문을 던진다. 우리는 어디에 있으며 어디로 가고자 하는지.

사유원, 고독의 공간

사유원은 시간과 공간의 기제로써 건축이 아주 독특한 맥락에서 작동하는 곳이다. 2006년에 시작하여 경상북도 군위군 부계면, 100만㎡의 산지에 조성 중에 있는 민간 공원이다. 극히 개인적인 계기로 출발한 사유원은 유재성 태창철강 회장이 오랫동안 가꾸어 온 꿈의 프로젝트다. 건축주는 자수성가한 기업가이자, 문화와 예술의 후원자이며, 고집스러운 이단아이기도 하다. 그는 “철강은 내가 하는 한가지 일이고 정원은 내 삶의 일부”라고 말하는 사람이다. 승효상은 2012년부터 참여하여 공원 내 여러 구조물을 설계했다. 처음 설계한 작은 전망대 집 ‘현암’, 연못 주변의 공연 공간 카페테리아 ‘사담’, 사유를 위한 야외 마당 ‘명정’, 계곡의 물 위를 거닐게 해주는 ‘와사’, 물탱크를 개조한 작은 망루 ‘첨단’, 주차장, 야외 화장실, 그리고 마지막으로 사유원에서 가장 큰 시설이 될 아직 지어지지 않은 호텔, 그의 사유원 작업들이다. 승효상의 파빌리온과 더불어 알바로 시자(Alvaro Siza)의 건축, 정영선과 카와기시 마쯔노부의 조경, 중국 서예가 웨이랑의 현판, 그리고 유재성 회장 자신이 곳곳에 조성한 설치들이 사유원을 구성하는 인공의 인자들이다.

사유원에 많은 시설들이 완공되었지만 아직 여기가 어떤 곳인지 규정하기는 어렵다. 이곳은 마스터플랜이 없는 거대한 공원이다. 마스터 플래너가 있다면 그것은 유재성이다. 하지만, 그는 우리가 통념적으로 알고 있는 일관된 마스터플랜을 갖고 있지 않다. 그에게 일관된 원칙이 있다면 그것은 자아실현일 것이다. 그러기에 논리와 계산으로 이해할 수 없고 많은 경우 놀랍고 과감하다. 그렇다면 사유원은 도대체 무엇인가? 사적 공간인가, 아니면 공적 공간인가? 영리를 추구하는 사업인가, 개인의 꿈인가? 사유원은 얼마나 커질 것인가? 이 곳의 건축이 하는 역할이 무엇인가? 사유원은 사람, 작업, 자연이 엮여 있는 아름다운 퍼즐이다. 건축주 자신을 포함하여 그 안에서 일을 하는 사람들을 미치게 만드는 수수께끼다.

사유원의 조성 과정에서 승효상이 발휘한 가장 중요한 미덕은 시간을 가늠하는 기다림의 자세이다. 마스터플랜이 없는 큰 공원이기 때문에 순서와 스케줄을 예측할 수 없다. 그래서 승효상이라는 ‘사람’은 불확실성과 갈등이 해소되고 어떤 결정을 기다린다. 때로는 적극적으로, 때로는 소극적으로 기다린다. 어떤 분야의 전문가라 하더라도 갖춰야 할 미덕이다. 더불어, 훨씬 더 긴 시간의 기다림이 승효상의 작업에 내재하고 있다. 인간이 상상할 수 있는 먼 미래에 대한 기다림이 사유원 파빌리온들에 전제되어 있다. 먼 미래 이들의 모습을 상상해본다. 지구가 겪고 있는 인류세의 진통이 지나간 후, 일군의 탐험가들이 군위를 찾아왔다고 상상해보자. 한 때 벌목하여 숲 속에 났던 길들은 일체의 흔적이 없어졌다. 탐험가들은 자연림으로 돌아간 계곡을 따라 올라가다가 와사의 코르텐 파편을 발견한다. 원래의 형체를 전혀 알 수 없는 철판과 우거진 숲을 거두면 바닥에 깔았던 콘크리트가 드러날 것이다. 한 때 이곳이 인공의 연못이었다는 것은 짐작할 것이다. 언덕의 봉우리에 올라가 허물어진 ‘명정’의 콘크리트 벽체를 보고 무엇을 위한 구조체였는지 고심할 것이다. 가운데가 비어 있는 구조체였다는 것을 짐작하겠지만 그것을 둘러싼 공간이 왜 있었는지 짐작하기 어려울 것이다. 저수지, 아님 하늘에 제사를 지내는 곳? 실용의 공간과 무용의 공간을 오가는 그들의 추측을 상상해볼 수 있다. 지형을 읽을 줄 아는 사람들이라면 얼마나 신중하게 지형에 자리를 잡은 것인지 알 것이다. 탐험가들이 아마 전혀 짐작하지 못하는 것이 있을 것이다. 이 구조체들이 애초에 폐허를 닮았다는 사실이다. [그림 7]

승효상은 하르부르크 반파시즘 기념비처럼 자신의 작업이 먼 미래에 사라질 것이라 전제한다.

죽음의 운명을 인간이 거역할 수 없는 것처럼 건축도 결국은 무너져 소멸하게 마련이다. 세운 자의 영광을 기리기 위해 제아무리 튼튼하게 만들었더라도 중력의 법칙에 끝까지 저항할 수 있는 건축은 세상에 없다. 남는 것은 오로지 기억이다.

나는 승효상을 실존주의자라고 생각한다. 인간의 유한성, 인간이 만든 사물들 또한 필연적으로 사라진다는 것이 그에게는 가장 중요한 존재의 사실이다. 인간이 인지할 수 없는, 하지만 분명한 신의 존재 앞에 선 인간의 유한성을 전제로 작업을 하는 건축가다. 물론 그가 설계한 건물들은 일상 사회 속에서 잘 작동한다. 그가 설계한 이런 좋은 건물마다 인간의 고독을 확인해주는 순간들이 담겨 있다. [그림 8] 사유원의 파빌리온들이 특별한 것은 인간과 사물의 유한성을 직접적으로 형상화했다는 점이다. 아렌트의 말을 다시 빌어오자. ‘이 세상에 공공 공간을 만들려고 한다면, 한 세대만을 위해 지어지고, 살아있는 이들을 위해서만 계획되지 않을 것이다. 그것은 유한한 인간의 생활공간을 초월해야 한다’. 사유원은 아렌트의 이런 생각을 실천한 셈이다.” 하르부르크 기념비, 노무현 묘역, 사유원 파빌리온이 보여주듯 인간이 만든 사물들은 서로 다른 시간의 리듬에 따라 변한다. 여러 하늘의 색조와 빛의 각도를 몸으로 느낄 수 있는 새벽에서 황혼까지의 리듬이 있다. 뜨거운 햇빛이 쬐고, 차가운 눈과 바람에 사물이 마모되는 계절의 리듬이 있다. 시간의 리듬에 따라 건축이 공적 공간과 관계를 맺는 방식이 달라진다. 사람의 활동적인 삶(vita activa)이 요구되는 시간이 있고 사람의 작업이 지속되는 더 긴 시간이 있다. 또한, 인간을 초월한 훨씬 긴 세월도 있다.

사물의 테이블에서

세계 속에서 함께 산다는 것은 본질적으로 사물의 세계가 이를 공유하는 사람들 사이에 놓여 있음을 의미한다. 마치 테이블이 그 주위를 둘러앉은 사람들 사이에 놓여 있는 것처럼 말이다. 사물의 세계는 사람의 중간에서 사람들 사이에 관계를 맺고 동시에 분리한다. 공동의 세계로서 공적 영역은 말하자면 우리를 하나로 모으면서도 서로에 기대지 못하게도 한다. 대중 사회가 견디기 어려운 이유는 연관된 사람의 수가 너무 많아서가 아니다. 적어도 그것이 주요 원인은 아니다. 사람 사이에 놓인 세계가 그들을 하나로 모으고 관계를 맺고 분리할 수 있는 힘을 상실했다는 사실이다. 기이한 상황이다. 테이블 주위에 많은 사람들이 모여 있는데 마술로 눈앞에서 테이블이 갑자기 사라진다. 결과적으로 맞은편에 앉아 있던 사람들이 더 이상 분리되어 있는 것도 아니고 서로 전혀 관련이 없는 사이가 되어 버린다.

승효상은 테이블을 설계하는 사람이다. 아렌트의 설득력 있는 비유처럼 테이블은 사물의 세계이다. 테이블의 디자인에 따라(테이블이 수평 기단임을 상기하자) 테이블 주위에 앉은 사람들의 관계가 바뀔 수 있다. 한편, 테이블 설계자로서 승효상은 자신의 가장 기본적인 역할을 다음과 같이 본다. 이 세계에 내던져진 유한한 존재로서 개인, 사회적 존재가 아닌 개인의 존엄성, 동시에 그의 고독을 확인하는 것이 자신의 역할이라고 본다. 다른 한편, 승효상은 자신이 테이블 설계자일 뿐만 아니라 사회 속에서 다른 수많은 사람들과 나란히 앉아 있는 한 ‘사람’이라는 것을 잘 안다. 따라서 사회 안에서 정치적 존재로서 테이블 주위에 둘러 앉은 사람들과 적극적인 관계를 맺으며 활동한다. 정치와 미학은 끊임없이 변한다. 어디든 마찬가지이지만 자유와 평등은 계속 지키고 가꾸어야 하는 가치다. 이런 인간의 조건 속에 건축의 역할이 있다. 그의 작업은 아름답기도 하고, 비극을 담아 내기도 한다. 미지의 미래를 가늠하는 풍광이다. 중요한 것은 그의 프로젝트가 말과 사유를 부른다는 사실이다. 테이블에 둘러 앉은 사람들이 관계를 가질 것을 요구한다.

승효상은 자신의 작업을 공공에 주어지는 것이라 생각하지 않는다. 동시에 공론의 장에 스스로를 내던져 일하고 있다. 이것이 도대체 말이 되는 일인가? 승효상은 끊임없이 어떻게 건축 작업과 사회가 공존할 수 있는지를 고민해 왔다. 그가 오랫동안 수도원, 수도적 삶의 공간적 질서를 건축의 모델로서 제시하는 이유다. 고독한 개개인들이 사회적 공동체가 아니라 그들이 도저히 가늠할 수 없는 존재의 세계 속에서 살아나가는 것이 수도원이다. 아마도 이 때문에 승효상은 자신이 좋아하는 한나 아렌트의 인용구에서 ‘공공에 작업을 내어놓는다고 얻을 수 있는 것이 아니다’를 언급할 필요를 느끼지 못한 것인지도 모른다. 승효상의 ‘활동적 삶’이 그의 작업과 공존하면서 그것을 풍성하게 해주는 것은 바로 사람과 작업 사이의 거리 때문인지도 모른다. 삶의 열정을 지닌 작업, 그것이 바로 아렌트와 더불어 키르케고르(Kierkegaard)와 야스퍼스의 실존주의를 하나로 묶어주는 것이다. 그들은 철학을 ‘인간의 양심과 진정성이 함께하는 현실에 개입하는 열정의 행위’로 인지했다. 우리는 승효상과 함께 이런 사유의 탁자에 앉아 철학 대신 건축에 대한 얘기를 나누기로 하자. 아렌트가 이미 강조한 것처럼 인간성은 테이블의 디자인만 아니라 이 탁상이 조성하는 공적 영역에 함께 앉겠다는 의지를 통해 실현될 수 있는 것이다.

Humanitas is never acquired in solitude and never by giving one's work to the public. It can be achieved only by one who has thrown his life and his person into the "venture into the public realm.”

Hannah Arendt, “Karl Jaspers: A Laudatio,” 1958

I begin with a quote from Hannah Arendt. It is a sentence from a celebratory address to her friend and former teacher, Karl Jaspers, on the occasion of his reception of the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade. In tune with the spirit of the Peace Prize, Arendt praised Jaspers for not only his work as a scholar but his simultaneous engagement in the public and political arena. It is an apt beginning to this essay because Seung H-Sang has in recent years used this quote to justify and explain his involvement in the public affairs of architecture and urbanism.2) Between 2014 and 2016, Seung functioned as the first City Architect of the Seoul Metropolitan Government and is presently the Chair of the Presidential Commission on Architecture Policy (PCAP). Through these positions, and certainly beyond these official appointments, he has been the force behind the creation of new institutions and policies that are changing the way architecture is practiced in Korea. The City Architect and public architect system are now part of almost all the major cities of Korea. With the vision of a rejuvenated public design system that engages with everyday life, he is changing the way public projects are procured, convincing policy makers to move toward neighborhood-based regeneration. He has been the primary force in the creation of the Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism, for which I served as inaugural director; a new kind of biennale woven together with the realities of urban governance. As Chair of the PCAP, among many major initiatives, he is pushing to abolish price bidding systems and subjective public review processes that impair the integrity and proper purpose of the architect’s design. Working with mayors and governors, cabinet ministers, and the President himself, his fingerprint can be seen in an array of public projects and policy initiatives. He is without doubt, the most influential architect in Korea.

It must be noted that before his recent engagements in the public sector, Seung H-Sang was already the most prominent architect in Korea. He is a prolific writer who has published manifestoes and best-selling books. He is the first and still the only architect to receive recognition as Artist of the Year by the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art. He is of course a prolific designer of buildings. Seung is the youngest of a post-colonial and post-fascist generation of creative architects. Born after the independence of Korea in 1945, this generation began their own practices when Korea became a democracy in the early 1990s and matured with the rise of Korea as a global economic force. I raise these points not merely to laud Seung as an individual architect but to point to the central question of this essay - the status of architecture in society as well as in the longer duration of human civilization. In engaging in this question, we return to Hannah Arendt and the quote that launches my essay. The key issue here – the relation between work and life - is in fact embedded in Arendt’s statement. I note that when Seung uses this quote, he usually omits the part “and never by giving one’s work to the public.” For the purposes of my essay, I underscore that we must take the full measure of Arendt’s statement. It is my argument that the distinction and relation between his “work” and “his life and his person” in the public realm is the key to understanding the architecture of Seung H-Sang.

In considering Seung as an architect, there is, on the one hand, the work: the buildings that he has designed and realized as things in physical space. On the other hand, there is what Arendt has called “personality,” that which must be thrown fully into the public realm. Following Arendt, the social theorist Kim Hyun Kyung provides the following definition of personality:

Personality is neither something we were born with (and thus have to try not to lose) nor an essence that has to be attained by socialization. Rather, we regard personality as something we have, something we feint having, one that exists by believing in each other’s play.

In other words, personality is a social phenomenon without essence. The person is formed only through the performance and interaction of individuals that form society. Seung indeed engages with a wide range of clients, media, and colleagues, forming a personality that is at once consistent and multi-dimensional. Each project, with a different role for Seung the person to play, has a different story to tell. Here, in this essay, I will give three examples of the different ways Seung, as the architect of a work and as a multi-dimensional person, engages in the architectural project. There are so many dimensions to Seung’s work and personality that I focus on one key aspect: the ground as both an idea and physical presence. In my 2007 book Sensuous Plan: The Architecture of Seung H-Sang, I had already stressed the platform, its expressiveness and its role in the organization of space. It is an aspect of his work that has been consistent during the past 25 years. I will also limit my discussion to just three projects – Pajubookcity, the Funerary Ground of Roh Moo-hyun, and Arboretum Sayoowon – divergent in program, scale, context, and client.

Pajubookcity as Cultural Landscape

The first is Pajubookcity, an industrial cluster for the publishing sector located 30 km from the center of Seoul and just 10km from the DMZ. First conceived of in 1989 as a response to an industry in crisis, a group of small-medium sized publishers led by Yi Ki-Ung devised the ambitious idea of a “book city.” The project went through several stages before a new direction was formulated in 1999 by the urban design team led by Seung H-Sang and Florian Beigel. The 1,600,000 ㎡ area of Phase 1 contains Korea’s largest distribution center, 130 publishing houses, 57 printers, and a hotel. With its successful completion in 2007, the second phase of Pajubookcity, in an area slightly smaller than Phase 1 and now including the film and media industries, is now fully in progress. Seung has several important built projects in Pajubookcity (such as the Design Vita Paju Office shown in pages 00~00), but his role in this major initiative, goes well beyond the traditional role of the architect-designer. His activity in moving Pajubookcity towards its present status as an innovative cluster involves an intense vita activa, the political and social engagement of the person.

Almost everyday for more than two months, Seung went to Paju for meetings with publishers, politicians, bureaucrats, and fellow architects. Seung planned architectural tours for the publishers, traveling together to change their sense of what architecture could do for their immense project. He set up seminars and workshops, curated exhibitions, all part of a process of convincing the publishers to implement a culture that moved away from existing conventions. As a result of all this activity, the publishers and architects agreed to a self-regulating design guideline, influenced by landscape urbanism but based on a series of architectural typologies and specifications for common spaces and building material. Publishers were further obliged to choose their architects from a select pool, a system that we now see implemented in the public architect system of municipalities in Korea. Even without ample resources, Pajubookcity has provided two generations of architects with opportunities to build, becoming an exhibition ground for the top architects of Korea and the world. With its infrastructure already laid out by the Korea Land Corporation’s conventional plan; as a neighborhood with just 160 units of housing; as a military zone prohibiting any structure over four stories; an industrial zone that disallows mixed-use, the architectural possibilities were in fact limited. Pajubookcity has nevertheless sustained its vision as an innovative city. [fig 1] With the changing relations between North and South Korea and the continuous expansion of the surrounding commercial and residential areas, it is expected to become an urban corridor for new social, political, and economic configurations.

If what I have just described about the nature of Pajubookcity revolves around the personality of Seung, we must at the same time highlight the architectural mechanisms employed within this social process. In this matter, Florian Beigel was Seung’s key partner, as it was the former’s ideas and sketches that provided the key inspiration in formulating the design guidelines. Beigel was constantly conscious of the different horizons that extend throughout the site - the horizon of the Han River, the level of the wetlands, and the expansive eye-level horizon of the viewer. [fig 2] As Joseph Grima noted in an article on Florian Beigel's Korean work, the "programmatic allocation throughout the [Paju Book City] occurs not in plan but in section." Certainly, before Seung’s encounter with Beigel, consideration of multiple topographic horizons was already a key aspect of the former’s work. It is a key character of architecture in Korea where, with its hilly terrain, buildings must carefully maneuver the different sections of an uneven, sloping land. Seung accepted Beigel’s scheme but his approach to these horizons was quite different. In contrast to Beigel’s phenomenological inheritance of an integrated horizon inherent within both the viewer and the object Seung approaches the horizons of Pajubookcity as historical and natural realities of the land. They should certainly be respected and followed, as his invention of the term “culturescape” implies, they are by no means universal. In other words, horizons are part of culture and formed through locality. This sensibility of multiple sections can be again found in his vision of Seoul as a multi-level city that encompasses its mountains and grounds as well as its artificial decks and underground spaces. [fig 3] As he reminds us, it is a sensibility rarely found in Western tradition of urbanism. For Seung, these sections and horizons are matters immediate to the site and immediately sensual. In this sense, he is not a fundamentalist.

The Funerary Ground of Roh Moo-hyun

and the Time of Things

As a single work, there is no other project that better tells the story of this entwinement of work and person than the burial ground of Korea’s former president Roh Moo-hyun. Roh Moo-hyun was the ninth President of the Republic of Korea and a revered leader of its democratic movement. Unlike former Korean presidents who went into protective urban enclaves after leaving office, Roh returned to his home village of Bongha. With his return, the small struggling farm village became a public site of the former-president's humble ambitions. It became a lively public landscape comprised of not only the former-president's private residence, farmlands, and working farm houses but also tourist shops and a refurbished museum house where Roh was born. Soon after his return to his home village of Bongha, his family and former aides became targets of investigations into corruption and influence peddling. Rather than face the humiliation of drawn-out legal procedures, rather than participate in the destruction of his legacy, Roh took his own life. In the early morning of May 23, 2009, he threw himself off Owl Rock, a steep hill next to his house in Bongha. Great controversy surrounds his life and death, but many have surmised that Roh believed that his death would preserve the force of his ideas.

Following his own wishes, Roh is the first former-president of Korea whose remains are not enshrined at the National Cemetery. Immediately after his death, a Committee for a Small Burial Stone was formed to realize the last wishes of the former-president. This committee selected Seung H-Sang as the architect of the funerary ground. It would not be an exaggeration to say that it was a kind of miracle that such a bold and consistent design was realized. Again, it is a testament to not only Seung as a person but the shared commitment of all those who came together in the aftermath of one of the most tragic events of modern Korean history. Following the participatory spirit of Roh’s politics, his funerary ground was created through the collaboration of artists, writers, scholars, and most importantly, the tens and thousands of people who left their messages of grief and hope in the 15,000 pavement blocks that comprise its pathways. Since its completion in the spring of 2010, millions have come to Bongha Village, making it a site of pilgrimage and tourism.

Like many of Seung’s projects, the essential aesthetic of the Roh Moo-hyun’s Funerary Ground lies in the way it builds a new ground into the fabric of the landscape. Once again, true to his edict of the "landscript," the architect sought to extract elements and boundaries from the ground. Existing waterways, roads and pathways, the existing contours of the surrounding mountains, the pattern of the adjacent farmlands provide the physical and intellectual infra-structure of the new site. Even the long corten wall, marking the boundary between the mountains and the funerary platform, can be seen as emerging from the conditions of the ground. The only element that yields to the vertical is a thick flag pole carrying a spot-light for the funerary stone. From his first sketches, Seung's dedication to building the ground is evident. The architectural task is to build a platform that is part of the ground and the landscape. [fig 4]

The orientation toward the floor, the aversion to the grandiose and the triumphant, would seem akin to the tendencies of the "counter-monument," a term coined in the early 1990s by James Young in his perceptive analysis of German Holocaust memorials. According to Young, the key characteristic of the counter-monument is the way it appropriates time: the way it understands that "Time mocks the rigidity of monuments, the presumptuous claim that in its materiality, a monument can be regarded as eternally true...It seeks to stimulate memory no less than the everlasting memorial, but by pointing explicitly at its own changing face, it re-marks also the inevitable - even essential - evolution of memory itself over time." Indeed, Seung often mentions Jochen Gerz and Esther Shalev-Gerz's sinking black pillar, the Harburg Monument to Fascism, as an important project that reminds us of the mortality of architecture. [fig 5] Compared to the Harburg Monument, the funerary ground has a longer rhythm of waiting. It waits with the hope that the footsteps that walk along the platform, eventually erasing the words engraved into the stone blocks of the platform, will form the "organized power of an awakened citizenry" - the words of Roh Moo-hyun etched onto the corten base of his funerary stone.

A Holocaust memorial is obviously very different from the burial ground of a former Korean president. Beyond their common critique of the everlasting monument, Seung's project brings a different approach to architectural forms. If the counter-monument works through a reversal of older traditions and a critique of context, Seung retrieves Korea's older traditions and reconciles his work with existing conditions of the landscape. Though the site may seem different and strange because of its departure from Korea's recent state-sponsored monuments, unlike the Holocaust monuments that sink and reverse, Seung's gesture is more of retrieval and rescue. Seung seeks inspiration from the low, horizontal platform of Jongmyo, the royal Confucian shrine of the Joseon Dynasty. Begun in 1394, this granite platform, 109m in width and 69m in depth, is indeed one of the great historic monuments to the way the ground defines the human condition. [fig 6] Seung's reverence to Korean tradition may further be read in the writing of the floor. In contrast to the Western tradition that equates civilization with the erect human figure distanced from the impurities of the ground, the Korean way of life sustains a variety of affinities with the floor. The words on the platform comprise less a critique of reading and more an affirmation of the Asian calligraphic tradition of horizontal writing. It is a project that relies, on the one hand, on a stable, conservative set of conventions. However, unlike Western traditions, it performs as architecture without the will to enclose and to build up.

This accommodating attitude toward older traditions is also present in the way the project finds its place on the land. Like the flat cultivated paddy fields of Bongha Village, the triangular platform enters the landscape as part of the existing field conditions. Like Pajubookcity, it is a cultural landscape. The low, flatness of the site preserves and amplifies the surrounding mountains that are the larger, more permanent containers of memory. Its essential humility lies in the way it opens up the view to Owl Rock, to Bonghwa Mountain, and to the open vistas that extend our mind and sensibilities beyond this small village. It understands that its architecture functions to provide an array of positions. You walk on it, look down to read, and kneel to pay your respects. Toward the mountains and from the mountains, it is a place both to see and to be seen. Without didactic arrogance, the funerary ground comprises a landscape that asks as us where we are and where we want to go.

Sayuwon and Solitude

The third and last project that I shall discuss, Arboretum Sayuwon, brings these mechanisms of time and place into a totally different setting. An ongoing project, Sayoowon is a private park, a 300,000㎡mountainous area in Gunwi, located in the south-east region of the Korean peninsula. First conceived in 2006 as a personal project, it is the dream child of Yoo Jae Sung, the President of the Tae Chang Steel Company. A self-made man, a patron of the arts, and a maverick, he has been quoted as saying that “Steel is one of the things I do, the garden is part of my life.” Since the spring of 2012, Seung has designed several structures within the park: Hyeonam, a small viewing house, the first of his designs to be built; Sadam, a cafeteria and waterfront performance stage; Myeongjeong, a contemplative outdoor water courtyard; Cheomdan, a small lookout tower renovated from a water tank; the parking lot; series of outdoor toilets; and finally, a hotel, the largest facility in the park and the only structure of his design that has not been built. They are structures that co-exist with the landscape designs of Jung Youngsun and several structures designed by Alvaro Siza, the most prominent of many artistic interventions within the vast site. Despite the sublime nature of its landscape, Sayuwon is characterized by its open, undefined nature as a facility. It is an enormous park without a masterplan. The only possible master planner is Yoo Jae Sung, who moves with the consistent purpose of self-fulfillment. They are bold moves that often defy logic and calculation. What is Sayuwon? Is it private or public? It is a commercial venture or a personal dream? What will be the extent of its development? Will the buildings have use or are they part of that rare species of useless architecture? Sayuwon is a beautiful puzzle, maddening for those who work in it..

Without going into the details of all of Seung’s projects in Sayuwon, I state that the architect’s most important capacity in this process is that of waiting, in all its different temporal scales. Seung the person and the work he produces wait, in the everyday sense, for uncertainties and conflicts to clear itself. Seung’s waiting extends beyond the practical matters of everyday patience, a virtue that is required in almost all professional practice. At the furthest extent of human cognition, it encompasses his sense of the finitude of not only man but also of the things he produces. Let us imagine the pavilions in Sayuwon as ruins. Imagine at some future point in time, perhaps in an era past the earth’s sufferings of the Anthropocene, a group of explorers venturing into hills of Gunwi. They will discover the mangled corten steel of Wasa, wedged into the concrete basin of what once used to be a pond. They will see the crumbled concrete walls of Myeongjeong and puzzled over what they were used for. If they are adept at reading the land, without knowing that it was the meticulous work of an architect, they may sense how carefully they were placed in the hills. These future adventurers will also not know that the original work looked very much like ruins. [fig 7]

As we have encountered with his appreciation of the Harburg Monument to Fascism, Seung approaches his work as a future ruin.

As man cannot deny the fatality of death, architecture ultimately falls down and disappears. No matter how firmly it is built to celebrate the glory of its patron, there is no building that can finally resist the law of gravity. What remains is only memory.

I believe Seung to be an existentialist. He is someone who believes in the profound finiteness of humanity and the mortality of its artifice; finitude in face of the unknowable but certain existence of God. While his buildings fully operate as part of the practical social world, his best work inevitably contains moments that confirm the solitude of man. [fig. 8] The pavilions of Sayuwon are exceptional in that they crystalize Seung’s sense of the finitude of men and things. We may certainly agree with Arendt and many others that “if the world is to contain a public space, it cannot be erected for one generation and planned for the living only; it must transcend the life-space of mortal men.” At the same time, as we have seen with the Harburg Monument, the Funerary Ground of Roh Moo--hyun, and the Sayuwon pavilions, man-made things take on different temporal rhythms. From dusk to dawn, there are the daily rhythms that bring forth different hues and angles of light. The seasonal changes of hot sun, snow, and wind accumulate to bring wear and tear to these things. Time thus affects the way architecture relates to the construction of public space. There is the time for vita activa and there is the longer time for man’s work in public space. There is also a time beyond humanity.

At the Table of Things

To live together in the world means essentially that a world of things is between those who have it in common, as a table is located between those who sit around it: the world like every in-between, relates and separates men at the same time…The public realm, as the common world, gathers us together and yet prevents our falling over each other, so to speak. What makes mass society so difficult to bear is not the number of people involved, or at least not primarily, but the fact that the world be-tween them has lost its power to gather them together, to relate and to separate them. The weirdness of this situation resembles a spiritualistic séance where a number of people gathered around a table might suddenly, through some magic trick, see the table vanish from their midst, so that two persons sitting opposite each other were no longer separated but also would be entirely un¬related to each other by anything tangible.

Seung is a designer of these tables, the world of things that Arendt speaks of in such an eloquent, metaphorical manner. Depending on the design of the table, and I remind our readers that the table is a horizontal platform, the relation of the people who sit around it may change. I would argue, on the one hand, that the most fundamental role of Seung as a table-maker is the affirmation of the simultaneous importance and loneliness of the individual - man, not as a social being, but a finite entity thrown into this world. On the other hand, Seung understands that he is not only the table-maker but is one of the individuals sitting side by side with many other different people in a mass society. He thus adheres to the idea of man as a political being within the confines of society. Politics and aesthetics are an ever-changing process, in Korea as in all places where freedom is as fragile as it is fundamental to the modern human condition. The projects that I have discussed are part of a landscape that is at once beautiful, tragic, and open to an unknown future. They call for language and thought; they ask the people around the table to sustain its relevance.

For Seung, work is by definition not something to be given to the public. At the same time, he has thrown himself to the agonism of the roundtable. This is why Seung constantly presents the monastery, the spatial order of monastic life, as the model of how architectural work and the social body may co-exist. Each individual, in the solitude of their existence in the world, come together less as a society but as finite beings within an existence that they cannot fathom. Perhaps that is why he did not feel the need to restate the phrase “giving one's work to the public” from the Hannah Arendt quote that he so cherishes. Perhaps, it is this very distance between person and work that allows Seung’s vita activa, to not just co-exist with but also nourish his work. Work that has the passion of life: that is what also brings Arendt, as well as the existentialism of Kierkegaard and Jaspers together. It was their sense of “philosophy as a passionate and deeply engaged activity, in which the integrity and the authenticity of the human being are decisively implicated.” We may bring Seung to this table of thought, exchanging architecture for philosophy. What is certain is that as Arendt has already underscored, humanity is achieved not just by designing the table but by the commitment to sit at the table of the public realm.

글. 배형민 Pai, Hyungmin 서울시립대학교 교수

배형민 서울시립대학교 건축학부 건축학전공 교수

‘생각과 글, 이미지, 공간, 설치 등을 엮어 관중과 소통하 고 다양한 사람과 협업하는 전시기획’의 재미에 푹 빠져 있는 배형민은 건축역사가이자 비평가이며 큐레이터이 다. 2008년, 2014년 베니스 비엔날레 한국관의 큐레이 터로 참여해 2014년에는 최고 영예의 황금사자상을 받 았다. 서울도시건축비엔날레 총감독, 광주 디자인 비엔 날레 수석 큐레이터, 국립아시아문화전당 협력 감독, 삼 성미술관 플라토 초대 큐레이터 등 전시 현장에서 활동 해왔다. 서울대학교 건축학과, 환경대학원에서 학·석사, MIT에서 박사 학위를 받았으며 서울시립대학교 건축학 부 교수다. MIT 프레스에서 출간한 《THE PORTFOLIO AND THE DIAGRAM》은 세계 유수 대학의 필독서이다. 《한국건축개념사전》을 공동 저 술·편집했으며, 승효상의 건축을 다룬 《감각의 단면》, 기업과 건축의 관계를 다룬 《아모레 퍼시픽의 건축》 등을 저술했다.

pai@uos.ac.kr

'아티클 | Article > 칼럼 | Column' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 03 우리의 수상授賞<상을 줌>이 수상受賞<상을 받음>보다 가치있기를 2019.12 (0) | 2023.01.07 |

|---|---|

| 중남미와 북유럽 여행 단상“여행은 나를 넓히는 연습, 나 자신 들여다보는 엄숙한 도정” 2019.12 (0) | 2023.01.07 |

| 나주 읍성 영금문 2019.10 (0) | 2023.01.05 |

| 01 우리는 사실 다 알고 있다 2019.10 (0) | 2023.01.05 |

| 02 좋은 건축 2019.10 (0) | 2023.01.05 |